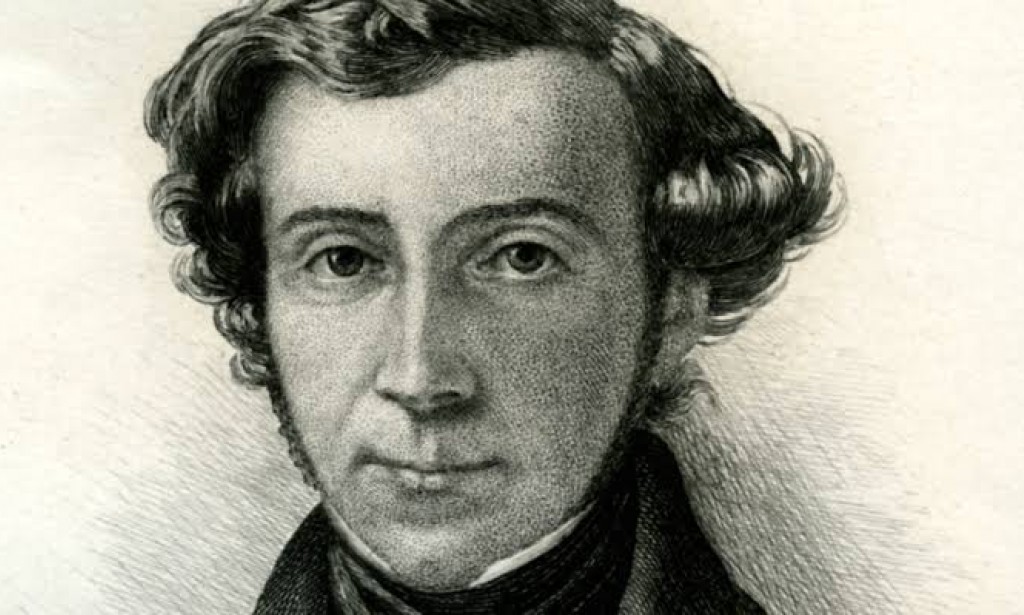

The Awful and the Extremely Terrible Considering Alexis de Tocqueville's oppressed worlds

"The whole book that you will peruse," composed Alexis de Tocqueville in the prologue to A vote based system in America (1835), "was composed under the strain of a kind of strict dread in the writer's spirit, created by seeing this overpowering transformation." This strict fear torment the two volumes of A majority rules government in America. What is the object of that dread?

It isn't "this powerful upset" itself. The "powerful upset" that Tocqueville saw was the "balance of conditions" — specifically, equivalent coercion of the person under the sovereign, in the regional country. The equity of coercion emerged when the sovereign was addressed by a Caesar or the crown, and it went on into Tocqueville's time.

The features of the sovereign changed, yet uniformity of coercion continued. This "transformation," Tocqueville wrote in 1835, "for such countless hundreds of years has walked over all snags."

Tocqueville doesn't go against the fairness of coercion. Nor does he propose protection from its brand new fair features. He acknowledges a majority rules system. He fears what the advanced vote based country state might deliver — for sure, was creating, particularly in France.

Tocqueville cautions of feared objects, to stir us to forestall or moderate them. America illustrated, to a certain extent, a portion of the deterrents, and Tocqueville believed the French should find out about them. However, in no way, shape or form was he certain that America would fight off those feared objects. In certain regards, America was farther along in showing up to them.

In the main perspectives, but — specifically, in the impulse and mores of centricity and the tremendous governmentalization of get-togethers — France was a long ways in front of the US.

Unfavorable alerts suffuse A vote based system in America and come full circle in the last piece of volume two, with the book's most well known section, "What Kind of Oppression Majority rule Countries Need to Dread." Here, that's what tocqueville pronounces "A more itemized assessment of the subject and five years of new reflections have not lessened my feelings of trepidation, but rather they have changed their item." Does he imply that the item has changed, similar to a structure that has been remodeled, or that another item lingers in his cognizance?

I propose two unique articles — the Awful and the Exceptionally Terrible.

The Terrible may be summarized as a stifling however gentle dictatorship of the "oppression of the larger part." The Awful is an oppression not just in light of the fact that assessment is overwhelmed by shallow, shortsighted doctrines yet in addition since that assessment calls government into steady extension and strength of get-togethers. Tocqueville calls it oppression regardless of whether the resident see it in that capacity, in light of the fact that far reaching, "overpowering" government isn't to the resident's advantage.

Here is "a power generally on its feet, keeping watch that my joys are quiet, flying in front of my moves toward dismiss each risk, without my expecting to consider it." This authority is "outright expert of my opportunity and my life," and it "corners development and presence." Tocqueville keeps up with that "The idea of outright power in fair hundreds of years is neither horrible nor savage, however it is minute and vexatious." It is an oppression, yet at the same one that "doesn't trample mankind."

In the section where Tocqueville discusses the changed article, he initially explains the prior object of his feelings of trepidation: "It appears to be that assuming tyranny came to be laid out in the majority rule countries of our day, . . . it would be greater and milder, and it would debase men without torturing them." Tocqueville discusses "a gigantic tutelary power" approaching over the populace, similar to an extraordinary "head master," looking to keep residents "fixed irreversibly in youth." It professes to ease them of "the difficulty of reasoning and the agony of living." The sovereign covers the outer layer of society "with an organization of little, confounded, meticulous, uniform guidelines." The sovereign "doesn't obliterate, it keeps things from being conceived; it doesn't tyrannize, it frustrates, splits the difference, exhausts, quenches, surprises, lastly lessens every country to being just a crowd of meek and productive creatures of which the public authority is the shepherd."

As of now, Tocqueville gets back to portraying the movement of authorial opinion: "I had consistently accepted that this kind of controlled, gentle, and quiet bondage, whose image I have quite recently painted, could be consolidated better compared to one envisions with a portion of the outside types of opportunity," including that the sovereign is "intently supervised by a truly chosen and free council."

Yet, Tocqueville goes to "just awful" conceivable article: when concentrated lawmaking and authoritative powers are left "in the possession of an untrustworthy man or body." He portrays what I term the Exceptionally Terrible: Residents "deny the utilization of their wills"; they lose "gradually the staff of reasoning, feeling, and acting without anyone else."

The Extremely Awful is the breakdown of law and order and the fixing of the fairness of coercion. Though the Terrible keeps a stifling, tutelary legislative power that subjects people generally and similarly, as per formally posted rules, the Extremely Terrible is a bad, maverick system wherein balance of coercion has vanished. An oppressive group practices government power inconsistent and faithlessly, to the extent that official regulations and methodology go.

Tocqueville closes the well known part with the accompanying passage, which includes an "vaporous beast" (the Terrible) however insinuates a potential ensuing beast (the Exceptionally Terrible):

A constitution that was conservative at the head and ultramonarchical in any remaining parts [that is, government organization being centralized] has consistently appeared to me to be a vaporous beast. The indecencies of the individuals who oversee and idiocy of the represented wouldn't be delayed to carry it to destroy; and individuals, burnt out on their delegates and of themselves, would make more liberated establishments or before long re-visitation of lying at the feet of a solitary expert.

Notice the expression "has consistently appeared to me." Tocqueville in this manner recognizes that the authorial gadget he has utilized — recounting a movement of authorial opinion since distributing volume one — is only that, an explanatory and educational gadget. Tocqueville saw the Exceptionally Awful while composing volume one.

Volume two expounds the Exceptionally Terrible

"In equitable social orders," Tocqueville states, "minorities can at times make [revolutions] . . . Majority rule people groups . . . are just conveyed along toward insurgencies without their knowing it; they in some cases go through them yet they don't make them." "The people who need to make an unrest [might] claim the hardware of government, all set up, which can be executed by an overthrow."

Discussing "[t]he tyranny of groups," Tocqueville composes of "a couple of men" who "alone talk for the sake of a missing and unmindful group . . . they change regulations and tyrannize freely over mores; and one is surprised at seeing the modest number of frail and dishonorable hands into which an extraordinary group can fall." Aggressive individuals looking to usurp protected government "experience incredible difficulty" doing as such "in the event that exceptional occasions don't come to their guide." The majority of the public conform: "[N]othing is more natural to man than to perceive unrivaled insight in whoever persecutes him."

Tocqueville expounds on the deficiency of concern, strict etc., for the future state: "When [persons] are once familiar with done being busy with what will occur after their lives, one sees them fall back effectively into a total brutish lack of interest to the future, [an indifference] that adjusts very well indeed to specific impulses of the human species . . . [T]he present develops enormous; it conceals the future that is being destroyed, and men need to consider just the following day." He proceeds:

Each becomes familiar with having just confounded and changing thoughts of issues that most interest those such as himself; one guards one's viewpoints severely or leaves them, and as one gives up all hope of having the option to determine without help from anyone else the best issues that human fate presents, one is diminished, similar to a quitter, to not pondering them by any means.

Such a state can't neglect to enfeeble spirits; it loosens the springs of the will and gets ready residents for bondage.

In addition to the fact that it then, at that point, happens that they permit their opportunity to be removed yet in addition they frequently give it over.

The sovereign "hence has a solitary power among vote based people groups, the general thought of which distinguished countries couldn't consider. It doesn't convince [one] of its convictions, it forces them and causes them to infiltrate spirits by a kind of gigantic tension of the personalities of all on the keenness of each."

Currently in volume one, Tocqueville plainly cautioned that "an extraordinary group can be persecuted without risk of punishment by a modest bunch of divisive individuals." The street is cleared by the tremendous governmentalization of get-togethers: "a sovereign power, that individuals . . . obliterates [institutions and customs] or changes them at its will." Individuals come to like "uniformity in bondage to imbalance in opportunity." The squashed resident "partakes in these merchandise as an occupant, without a feeling of proprietorship." Any "hopeless individual" can comprehend "denying the public depository or selling favors of the state for cash . . . also, can compliment himself with doing as much in his turn."

Might legitimate decisions at any point be kept up with? "The risks of the elective framework in this way fill in direct extent to the impact applied by the chief power on issues of state." "[T]o wish . . . that the delegate of the state stay outfitted with a huge power and be chosen is to communicate, as indicated by me, two inconsistent wills."

يجب عليك تسجيل الدخول لتستطيع كتابة تعليق